Why this matters

Families with relatives in care homes have been separated during COVID-19: to protect lives, protect the NHS and reduce the spread of the virus. However, this has resulted in significant harm, and unintended consequences, with them disproportionately affected. Restrictions at the time of writing have lasted nine months.

Our research, carried out between May and October 2020, focuses on the impact of this on family carers with older relatives in Scottish care homes: the partners, husbands, wives, sons, daughters, close friends or family members with primary caring responsibilities. Drawing on the evidence, it makes recommendations to reduce harm, reconnect families and recognise them as essential partners in care. Learning from their experiences, it also draws out lessons for the future, to ‘build back better’ and prevent this from happening again.

The study recognises the significant pressures on care home staff, and aims to promote and raise awareness of the relationship-based practices that make a positive difference, the creative responses that have helped and where digital technology can contribute. It identifies the changing roles that staff have played during the pandemic in supporting residents in life, and in death when family members have been unable to be there.

Recommendations identify actions to support families, and inform the Independent Adult Social Care Review, as Scotland considers the need for and shape of a National Care System ahead of 2021 elections.

Research in context

Landscape of restrictions

Globally, governments have restricted visits to care homes in response to COVID-19. The UK Government initiated a national ‘ lockdown’ on 23rd March 2020. In Scotland, some care homes closed their doors as early as the 11th of March.123

Restrictions have ranged from no visiting at all, to some ‘easing’ as recommended in Government guidelines (from July through to November 2020). These also called for sympathetic consideration of ‘essential visits’ which might include ‘circumstances where their loved one may be deteriorating, where it is clear that the person’s health and wellbeing is changing for the worse, where visiting may help with communication difficulties, to ease significant personal stress or other pressing circumstances.’4

Government has also signalled its intention to expand testing for designated visitors with more local oversight and ownership within a national guidance framework, learning from pilots. Recognising the importance of safe indoor visiting over Christmas and New Year as crucial to the wellbeing of residents, family and friends, guidance has also been issued to support safe indoor visiting where this has not been achieved. Testing is a key part of this, with the vast majority of care homes due to receive rapid testing kits for visitors from 14th December 2020. The few care homes not receiving these kits will be offered additional PCR testing instead.

Announcements have also been made that care home residents in Scotland will be able to receive the Pfizer/BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine from 14 December 2020.

In the meantime, visiting in care homes is subject to care homes being free of any COVID-19 symptoms for a designated period, participating in the care home testing programme and risk assessments being approved by the local Director of Public Health5 (Scottish Government, 2020). The 28 day quarantine period after an outbreak that has been in place for many months, was reduced to 14 days from the start of December 2020 following advice from Sage. Public Health is also required to confirm that each outbreak is over.6

Care homes can exercise discretion in following guidance. It is important to note that care home relatives and residents are not able to exercise the same levels of discretion that care homes, or indeed, other citizens have been afforded since March 2020. The UK relaxation of restrictions over Christmas, 23-27 Dec 2020, does not apply to visiting people in care homes and residents.

Scale of the problem

Never before has visiting been restricted for so long or affected so many families who are also at a vulnerable point in life.

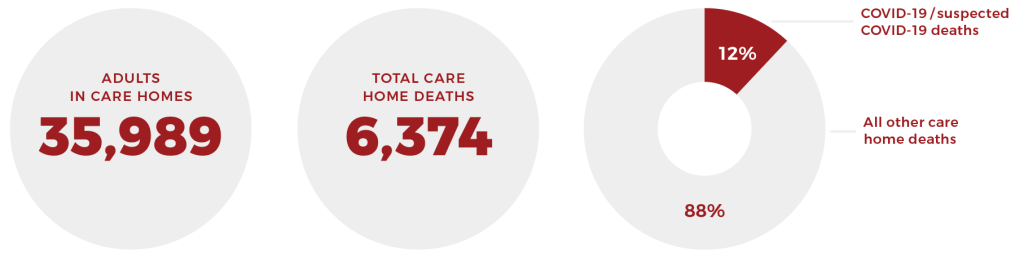

There are around 36,000 (35,989) adults in care homes in Scotland based on the latest figures for 31 March 2017 and 91% of them live in older people care homes.7 68% of residents are women with a median age of 84, 60% require care from a registered nurse and 49% have a diagnosis of dementia. Around 60% also fund their own care8 with costs especially high for those with dementia as highlighted by the Fair Dementia Care Commission.9

Of all deaths in Scotland attributed to COVID-19, 47% have occurred in care homes.10 During the first wave of the pandemic (mid-March-mid-Oct 2020), there have been 2,184 (31%) more deaths in Scottish care homes than normal during these months according to records. Of these excess deaths, coronavirus was the underlying cause in 1,898 (87%).11

But death is no stranger to care homes in ‘normal’ as well as ‘COVID times’.

- Just under half of all care home residents are admitted from hospital (46%)7

- The median time people live in a care home before dying is around 1.6 years7

Between 25 May and 6 December 2020, based on weekly reporting to the Care Inspectorate12 we know that:

- 6,374 care home residents have died

- 785 have died of COVID-19 or suspected COVID-19

- 5,589 have died of ‘other causes’ – 88% or approximately nine out of 10 care home deaths

This means that thousands of care home residents have been deprived of contact with family members in their last weeks and months of life, many without them by their side.

Care home deaths during pandemic

What the research involved

This rapid six-month study took place between May and October 2020 using mixed methods study design:

- An online survey – completed by 444 family carers – General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) indicators measured carer’s mental health and wellbeing, exploring its relationship to visiting restrictions. This was completed between 3 August and 21 Sept 2020, with respondents from 31 out of 32 local authorities in Scotland.

- 36 in-depth interviews with family carers of older care home residents.

- 19 semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders – a range of sector leaders and policy actors from Scottish Government, regulatory authorities, care home sector, Regional Health and Social Care Partnerships, third sector, advocacy organisations and Industry.

- Five café style interviews – involving groups of staff from four care homes – to identify positive and creative practices supporting connection and communication for the benefit of families. The four care homes involved were all from the independent sector and employed nurses on site. All but one had experienced deaths from COVID-19.

There is opportunity to build on this work to: engage with more staff from a wider range of care homes (including those without on site nurses); learn more about the experiences of family carers from diverse backgrounds, including BAME and LGBT+ groups.

Key findings

Carers are experiencing significant mental distress

‘Lockdown’ or social distancing has affected the mental health of many citizens. However, the mental health scores for family carers with relatives in care homes, are significantly poorer than those of the general public.

- 76% of family carers in our survey had a GHQ score of 12 points or more – with 12 marking the threshold for ‘clinical mental distress’

- Family carers had an average GHQ score of 18.16 (in contrast to GHQ scores of 12.7 for the general public during the pandemic) – the GHQ scale runs from 0-36

We also know from our survey, that women scored significantly higher than men, and partners of relatives in care homes more highly than children of relatives.

Frequency of usual visiting affects GHQ scores too. Family carers who had visited more than once a week or every two weeks before restrictions, scored more highly on average than those who had previously visited weekly, monthly or less often.

Mental health of carers during pandemic

From our survey, we can also say that carer’s mental health has declined since visiting restrictions came in:

- 74% agree or strongly agree that they are preoccupied by thoughts of their relative’s wellbeing – 32% and 42% respectively

- 66% were ‘more stressed’ since COVID-19 visiting restrictions were introduced (30% said ‘about the same’)

- 63% were losing sleep over worry ‘rather more’ or ‘much more’ – 36% and 27% respectively

- 58% were ‘rather more’ or ‘much more’ unhappy and depressed than usual – 21% and 37% respectively

Carers’ views on visiting restrictions

Levels of support

Just over half (51.4%) of care home relatives surveyed agreed ‘to some extent’ with government policies restricting visiting to care homes (27.9% disagreed to some extent, and 10.7% neither agreed nor disagreed). Family carers with a spouse or partner in a care home were significantly more likely to oppose visiting restrictions than other relatives.13

From fear to frustration with policies

Support for visiting restrictions has waned. Family carers completing the survey in later weeks were significantly more likely to believe that visiting restrictions were wrong.14 Why? We know from interviews that as restrictions stretched into months, not days or weeks, that many who had once supported restrictions, changed their minds. Many felt that the psychological harm caused by separation, outweighed the risks of the virus; that the right to a family life had not been adequately balanced against the risks of infection.

Waning support also coincided with the re-opening of parts of the economy that had been closed, the return of students to schools, colleges and universities, with this generating confusion and distrust around the rationale for policy-maker’s decisions. Many felt older people had been forgotten, with the re-opening of care homes, not seen as the priority they felt it should have been, compounding the invisibility of older people in care homes and in society more generally.

A matter of trust

Family carers who felt visiting restrictions were wrong were significantly more likely to report that they had lost trust in others (54.5%) when compared with those who supported or were neutral towards policy (39.3%).

Those who felt well-informed by the care home about the health and wellbeing of their relative, were significantly more likely to support visiting restrictions.

The emotional toll on relatives

Fear and loss

‘Visits’ carry multiple meanings, and their loss is profound. In interviews, family carers expressed loss and grief at being separated; fears about the decline of their relative’s mental and physical health as a result of separation (especially for those with dementia or degenerative conditions); fear that they would never get back the lost or remaining ‘good days.’ They expressed fears that ‘time was running out’ for them to be together. They also worried that the needs of their relative would go unmet without them being there to pick up on or voice any concerns.

Absence of touch

The loss of touch and sensory contact had a profound effect on people. Not being able to hold their relative’s hand or hug them was very upsetting for families.

A tough time made worse

For family carers, the transition from being a relative’s primary carer to a new role following their admission to a care home, is important to understand. Behind this move, difficult decisions have had to be made, with family carers experiencing complex emotions – grief, loss of motivation, loneliness and guilt, as well as positive feelings of relief and reassurance that a care home can provide the level of care that they cannot. Visiting restrictions serve to exacerbate those feelings. Plus, for those, who have built routines around visiting the care home and view staff as ‘friends’, they miss the community provided by those connections.

A matter of status

The term ‘visitor’ (as used in ‘visiting restrictions’) is problematic, and considered an inaccurate description by relatives of what they do and who they are. It disguises the significant part they play in delivering direct care, and the primary loving relationship that defines their connection. Like most family relationships, it is premised on unique and complex histories that provide knowledge essential to delivering ‘person-centred care’ and working as effective ‘partners in care.’

Unfortunately, most policy makers and leading figures in the sector only had a superficial understanding of the impact of restrictions on family carers, with little acknowledgement of family carers as partners in care and the symbiotic relationship between care-giver and care-receiver. They recognised that the pandemic had shown how little society values older people. Some family carers in our study expressed the desire to be allocated ‘key worker status’ to enable them to go into the care home and provide care to their relative. This is also echoed by a number of carer advocacy groups, including Care Home Relatives Scotland.

Experiences of care home staff

Mutual empathy and respect

In the main, family carers expressed support and admiration for care home staff, recognising the stress they were under, while staff had empathy for relatives separated from those they love.

Prior trust in care home management, staff’s track record in going ‘above and beyond’ to show genuine care for their relative all mattered immensely, as did frequent and effective communication during restrictions. This helped family carers remain confident that their relative was in the best place. In contrast, some families were rethinking whether a care home was in fact the best place for their relative.

Increased workload and exhaustion

Visiting restrictions meant significant reduction in the care families could provide at the same time that staff were trying to work through changes and respond to increased calls from family carers about their relatives. At the start of restrictions, staff received many calls from multiple family members, seeking reassurance. Admitting new residents during lockdown was also identified as particularly challenging, with family members unable to provide care and relationships between care home providers and families harder to build over Zoom!

Tensions

Staff reported families becoming frustrated with them, ‘pushing boundaries’ and challenging wearing of PPE, avoiding touch or rules around gift giving; whilst some relatives felt surveilled during time-restricted garden visits. Staff also recognised in-built inequalities with some residents on the ground floor able to have window visits, while others on different floors could not.

Staff were worried for their own safety too, and felt some family carers were ‘not getting it really, that this is all about footfall, and like it or not we’re at more risk’.

Changing roles of staff

Part of the extended family

Some staff spoke about becoming an ‘extension of the family’. They found themselves holding a phone to a resident’s ear and facilitating final conversations before a person died – being present during intimate conversations that would once have been private. They held the hands of residents when dying – because family members could not – either because they lived a long way away or were shielding.

Staff also played an important role in upholding rituals – with examples of staff showing respect as a hearse carrying a resident passed by. Others celebrated important birthdays with residents, and set up video links so family members could attend.

Accelerated learning and leadership at all levels

The pandemic accelerated learning and leadership at various levels within care homes in our study – prompting younger staff to feel more confident in taking part in conversations between families and residents, or taking a lead in setting up video calls (because they more often had the know-how). Significantly, there was also a greater appreciation of everyone’s assets as people ‘pulled together’ leading to more agile and better team working and a flattening of traditional hierarchies. People felt empowered to be creative. Staff talked about feeling more valued.

Technology’s role

Technology has played a considerable role during visiting restrictions: video calls have helped family members speak to and see loved ones, and helped staff build relationships with families. Care home ‘Facebook’ pages have also provided a ‘window into the world of the home’ to reassure relatives at a distance. Online spaces have supported family carers to connect with and support one another.

However, we need to be mindful that technology is not a panacea, but needs to be ‘right’ for individual families, and able to be supported by staff. For example, a video call to a resident with dementia may leave them more distressed and confused, not happier. For others, it will be a real joy seeing family members on screen. Staff will also require know-how in setting up a video call; many do not have this. ‘Low tech’ methods of communication like letter writing or phone calls might work better for some residents – those with poor eyesight or hearing difficulties for example.

Policy-makers and senior stakeholders were keen to promote digital technology, while recognising it was not sufficient in maintaining a sense of contact between family carers and care home residents. Policymakers also need to recognise and address digital exclusion.

Conclusion

Older people in care homes and their families have suffered real emotional pain and psychological distress, and have been disproportionately affected during the pandemic. It is likely that the effects of this will be felt for years, especially in cases where a relative has died.

Many family carers felt that the human right to a family life had not been adequately balanced against the risks of infection, especially when restrictions turned from weeks into months.

National guidance has been difficult to follow and implement consistently, equitably and proportionately across the care home sector. There are many reasons for this. However, decisions need to be transparent and explained, not to further damage trust. We are also mindful that care home relatives and residents are not afforded the same levels of discretion or decision-making powers that care homes, or indeed other citizens have.

Sadly, this study has highlighted how little we value older people in our care systems and processes, and the need for policies to give attention to equality of impact on marginalised groups. It is also the case that family carers do not get the recognition they deserve – with low status associated with female and caring roles. This is true for unpaid family carers, and for waged care staff.

Most family carers expressed support and admiration for care home staff, recognising the severe stress they were under. Staff have experienced increased workloads, managed tensions and boundaries around visiting, and found new ways to maintain connection and communication to support families. This has seen them stepping into different roles as ‘extended family’ members, and provided examples of agile and creative team working and initiative. However, care home staff cannot replace a resident’s own family.

Key recommendations

- There is a need for greater stakeholder involvement in shaping policy involving relatives, carers’ organisations and care home providers, with emphasis on coproduction.

- The contribution and status of family carers needs to be elevated, with them recognised by everyone as true partners in care and not ‘visitors’; policymakers awarding them ‘key worker status’ as family carer advocacy groups are calling for, would achieve that.

- We need to elevate care worker’s status and seriously invest in jobs, careers and training, with a focus on relationship-based practice, and promotion of learning, creativity and leadership at all levels.

- Peer support provided by family carers has been a powerful force during the pandemic – both as a tool for advocacy and for practical and emotional support. Care homes should consider the role they can play in facilitating communities of support.

- There needs to be focus on a human rights-based approaches, which address ageism along with discrimination experienced by other marginalised and minority groups. Inequalities will be exacerbated in times of crisis, and we need to be better prepared for the future. Policymakers should adopt the PANEL principles supported by the Scottish Human Rights Commission.

- Policymakers need to acknowledge the pain and loss experienced by families of care home residents, and the disproportionate impact on them to help rebuild trust.

These recommendations are offered as a way to ‘build back better’ and learn from the experiences of the pandemic.

Footnotes

- Meiklem, PJ (2020) ‘Coronavirus: Tayside care giant bans visitors – including family – to prevent virus spread’, The Courier, 11th March.

- Paterson, S (2020) ‘Care homes in Glasgow restricting visitors in a bid to protect residents from COVID-19’, Glasgow Evening Times, 13th March.

- Hill, A (2020) ‘ Care homes ban family visits to stem spread of coronavirus’, The Guardian, 13th March.

- Scottish Government (2020) Coronavirus (COVID-19): adult care homes guidance, 12 Oct 2020. [accessed 3/12/2020]

- Scottish Government (2020) Adult Social Care Winter Preparedness Plan 2020-21

- This was confirmed in a letter dated 2 Dec 2020, after Scottish Government announced publicly on 17 Nov 2020, that this was to be reviewed

- ISD Scotland (2018) Care home census for adults in Scotland https://bit.ly/3a3nWOu

- Burton K, Lynch E, Love S, Rintoul J, Starr JM and Shenkin SD (2019) Who lives in Scotland’s care homes? J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2019; 49: 12–22 | doi: 10.4997/JRCPE.2019.103

- Fair Dementia Commission (2019) Delivering fair dementia care for people with advanced dementia, Alzheimer Scotland

- Bell D, Comas-Herrera A, Henderson D, Jones S, Lemmon E, Moro M, Murphy S, O’Reilly D and Patrignani P (2020) COVID-19 mortality and long-term care: a UK comparison, International Long Term Care Policy Network

- NRS (2020) Deaths involving coronavirus (COVID-19) in Scotland: week 41, published 14 October 2020. National Records of Scotland. [accessed 3/12/2020]

- Scottish Government (2020) Coronavirus (COVID-19): adult care homes – additional data [accessed 3/12/2020]

- The gender of carers, how often they had visited before restrictions, or how long their loved one had been a resident were not significant factors in determining their support for visiting restrictions

- The survey was completed between 3 August and 21 September 2020

PDF download